This tropical tree has evolved to defeat its ‘enemies’ — with lightning

Lucky strike.

Lightning is often seen as a killer, leaving behind destruction and death of trees — but one tropical species has evolved to use the force of nature to its benefit.

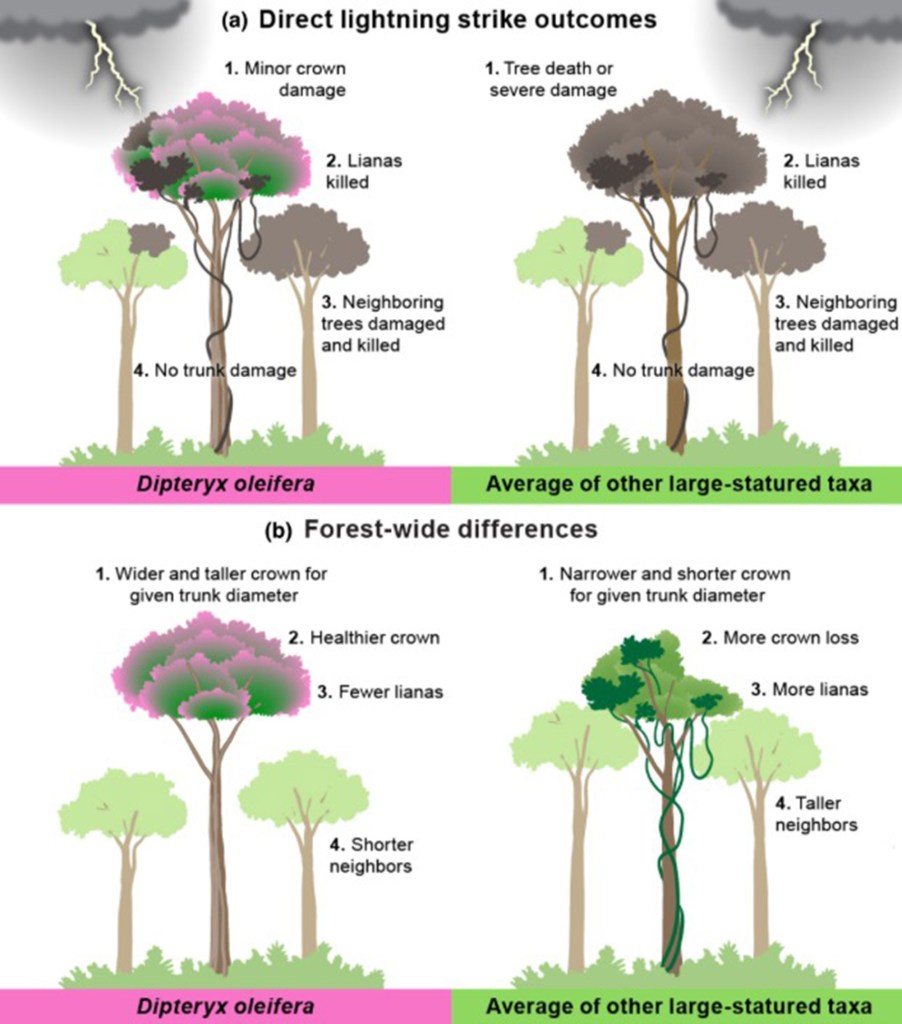

The tonka bean tree, scientifically known as Dipteryx oleifera, has developed the ability to not only survive strikes but also to transfer the electricity from lightning to its “enemies” and the parasitic vines that cling to the tonka bean trees, according to a new study in .

Lightning is largely a cause of tree mortality in tropical forests, especially when it comes to the largest and oldest trees that play a big role in storing carbon and supporting biodiversity.

But even with all the wreckage, researchers noticed that one tree species seemed to be left unscathed — and thriving.

“We started doing this work 10 years ago, and it became really apparent that lightning kills a lot of trees, especially a lot of very big trees,” Evan Gora, lead study author and forest ecologist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, . “But Dipteryx oleifera consistently showed no damage.”

Researchers analyzed nearly 100 different lightning events in Panama’s Barro Colorado Nature Monument using a custom-built system with electric field sensors and cameras to track lightning strikes. They also studied decades’ worth of tree plot records.

Scientists developed a high-resolution detection system by placing an antenna array throughout Central Panama, which detected radio waves of from the jolts of electricity.

They were able to triangulate the strikes with high accuracy by studying the energy patterns recorded. Combined with on-the-ground surveys and drone imagery, researchers could pinpoint the area of the forest that was struck and continue to monitor the tree conditions over time.

The tonka bean tree stood out to researchers as one species that consistently showed little to no damage after a lightning strike.

“Over those 40 years, there’s a quantifiable, detectable hazard of living next to Dipteryx oleifera. [As a tree], you are substantially more likely to die than living next to any other big old large tree in that forest,” Gora said.

According to the findings, each strike of lightning killed more than 2.4 tons on average of nearby tree biomass and 78% of the parasitic vines that attached to the tonka bean tree’s canopy.

The physical structure of the tonka bean tree is likely behind its resistance to lightning, Gora speculated.

These trees tend to grow tall and large, up to 130 feet, and live for centuries, meaning that a single tonka bean tree is believed to be struck by lightning at least five times after reaching maturity, and each strike helps in taking out vines and competitors — helping it thrive and increase its lifespan.

Being struck by lightning could result in a 14-fold increase in lifetime seed production, the researchers said.

Gora and the team of researchers are hoping to continue their research, expanding to other forests in Africa and Southeast Asia to see if there are any other species that benefit from lightning strikes.